David Loker

February 12, 2026

8 min read

February 12, 2026

8 min read

Cut code review time & bugs by 50%

Most installed AI app on GitHub and GitLab

Free 14-day trial

Predictions about the end of programming are nothing new. Every few years, someone confidently announces that this time developers are truly finished.

If you listened to these self-proclaimed Nostradamuses, devs were previously set to be replaced by everything from compilers ("If a machine writes the instructions, what's left for humans to do?") to low-code, no code tools ("Why hire developers when your VP can drag-and-drop an enterprise app?") to visual programming (“It looks like a flowchart, so it’s going to eliminate programming altogether).

This time, the executioners are AI coding agents.

Executives, founders, and tech influencers are lining up to tell the world that software engineers are living on borrowed time, that within a year or two, AI agents will write all the code, humans will step aside, and “developers” will join the long list of roles rendered obsolete. Like telephone switchboard operators or video rental clerks.

They’re not entirely wrong. AI will indeed write much more of the code in a year or two, maybe even all of it for certain kinds of tasks. But rest assured, those sharing these takes are coming to the wrong conclusions.

The phrase “the king is dead, long live the king” dates back to medieval Europe. It was announced at the moment of a monarch’s death to affirm continuity: one king has fallen, but the institution of kingship lives on in his successor.

Applied to software engineering, the message is similar. The old model of developers is, indeed, dying out. In a few years, you won’t find devs who spend their days hand-writing syntax and carefully constructing every loop, import, and conditional.

But the developer role itself isn’t disappearing. This isn’t an extinction event, it’s a succession.

The historical track record of “developers are finished” takes isn’t great. Every new abstraction triggers the same Twitter and media discourse: confident pronouncements, sweeping generalizations, and a level of certainty usually reserved for end-of-the-world cults. And yet, somehow, the world keeps running.

In hindsight, these predictions look less prophetic and more like Silicon Valley’s version of Chicken Little.

The story always ends the same way: declare developers dead, dramatically increase the demand for software, and then hire more developers than before. Only now, with better tools and bigger problems.

Because the thing people forget is that each time abstraction rose, developers adapted. As Grady Booch put it on X recently:

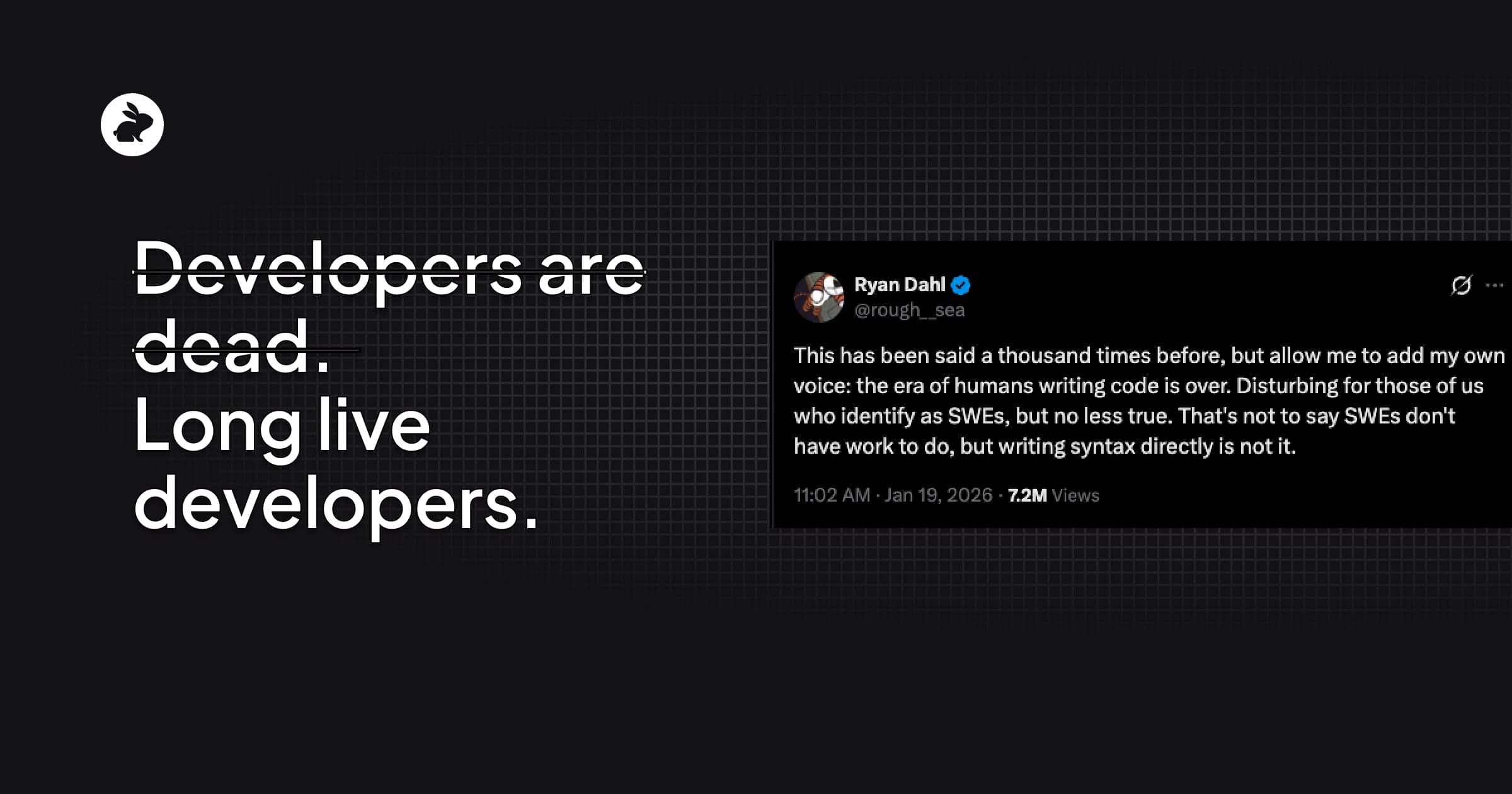

Others have been more blunt. One widely shared take summed it up this way:

If you squint, these statements sound apocalyptic. But read carefully, and they’re actually saying something very different.

They’re not claiming engineers stop existing. They’re claiming how software gets written is fundamentally changing. And they’re right.

AI is getting very good at generating code. Large chunks of application logic that once required careful human authorship can now be produced automatically. Boilerplate, glue code, scaffolding, even moderately complex algorithms are increasingly cheap to generate.

That means some code simply won’t be written directly by humans anymore in the future as AI improves. But not all of it. Even in a world where AI coding bots could potentially take over your job completely, they likely wouldn’t be trusted with things that we prefer human judgement around like:

Critical systems

Performance-sensitive paths

Novel architectures

Ambiguous or underspecified domains

These still demand deep human judgment. And even when AI writes the code, it doesn’t mean the human role disappears.

It just shifts.

One tweet captured this change succinctly:

This is the uncomfortable truth about AI code generation: it is extremely confident, often persuasive, and occasionally very (elegantly) wrong.

Catching those failures requires more, not less, expertise.

You don’t review AI-generated code by just checking syntax. You review it by asking:

Does this match the intent?

Are the assumptions sound?

Does this fail safely?

What happens at the edges?

Is this maintainable six months from now?

That’s not junior work, that’s senior judgment.

And while we at CodeRabbit have created AI code reviews to help make the job of parsing AI code easier and catch bugs humans often miss, we don’t claim to be able to take a human out of the loop.

A human developer is critical for catching business logic mistakes and other key nuances that AI isn’t able to. We just make their job of reviewing large volumes of AI generated code less overwhelming and, therefore, capable of scaling.

As AI systems take on more of the work of producing code, the most important human contribution shifts upstream. Code validation won’t start at the PR stage anymore, it will start before the code is actually written by reviewing the intent and plan.

This is where prompt reviews are set to become central.

With AI writing most of the code, developers will increasingly focus on things only they can do like:

Decomposing ambiguous problems

Understanding business goals or feature design

Specifying interfaces and acceptance criteria

Defining constraints and non-goals before anything is generated

Providing the right context at the right time

Building tight feedback loops

Designing for safety (security, privacy, reliability)

Setting success criteria that can be evaluated after the fact

Reviewing outcomes against original goals, not just surface correctness

That’s a lot of work when teams have to keep pace with the speed of coding agents. And that involves being extremely clear about intent early on and ensuring alignment.

After all, misunderstood intent or lack of alignment is what causes rework and delays at the PR review or testing stage. Ambiguity is what produces brittle systems. Poorly articulated goals are what lead AI to generate large volumes of code that look reasonable, behave correctly in the happy path… and quietly miss what actually matters.

Prompt review is therefore set to become a key part of the SDLC in the next few years where alignment is validated before generation. That will involve:

Checking whether assumptions are explicit or merely implied

Making tradeoffs visible instead of accidental

Ensuring that “done” is defined, not guessed at

Validating that the output matches intent

In that world, planning and review converge into a single responsibility: shaping the problem so the system has a chance of solving the right one.

The developers who thrive won’t be the ones who can coax the most lines of code out of a model. They’ll be the ones who can express intent precisely, recognize when outputs drift from it, and intervene early as a team to get alignment, before small misunderstandings scale into large, expensive failures.

This shift toward an intent-first workflow isn’t theoretical for us. It’s what we’ve been seeing play out with teams using CodeRabbit.

As AI accelerates code production, we’ve increasingly seen bottlenecks at the code review stage due to the volume of code AI was helping write and the number of issues it was adding to that code. Our recent study found that AI added 1.7x more bugs and issues to code than humans did.

But, from what we saw, we believed that the real problem wasn’t just AI coding agents but how teams were working with those agents. Prompts were vague. Assumptions were implicit. Context lived in people’s heads or scattered Slack threads. Often AI was left to fill in the gaps and did so confidently but wrongly leading to more work at the review stage.

What’s more, there was now a cold start problem where it became onerous and time consuming to draft the requirements into a prompt in a way that included all the assumptions, specs, and context so that AI could actually understand and properly execute on the code.

That’s the problem that our CodeRabbit Issue Planner and Coding Plan feature are designed to address. They support developers in turning ideas into concrete, reviewable plans that are digestible by AI coding agents. They surface assumptions, clarify scope, define constraints, and make tradeoffs explicit before generation begins.

Importantly, these products don’t make judgment calls on behalf of developers like a coding agent might do if it made a plan itself. They don’t decide what “good” looks like. They don’t replace architectural thinking or product understanding. They create an editable first draft of a prompt that can be reviewed by anyone on the team to create space for alignment and visibility earlier and to help support decisionmaking.

That’s because as code generation becomes faster and cheaper, the value of developers concentrates around intent, judgment, and alignment. CodeRabbit’s planning products are built to support that reality. They help developers focus more on judgement and strategy, help catch misunderstandings sooner, and stay firmly in control of how they use AI in order to improve output and reduce rework later on in the development process.

Somewhere right now, a CEO or two is likely polishing keynote slides about “the end of developers.” If history is any guide, they're going to be very disappointed.

Not because AI won’t change software engineering (it already has) but because they’re mistaking a transformation for an extinction. What’s ending is a particular image of the developer: hunched over syntax, manually assembling every loop and conditional, measured by lines of code and hours spent typing.

But the role of developer isn’t vanishing. It’s shedding a skin.

The future developer:

Works at higher levels of abstraction

Defines intent rather than typing syntax

Reviews systems and outcomes, not just lines of code

Acts as the final arbiter of correctness, safety, and alignment

As AI takes over the mechanics of production, more responsibility, not less, falls on the humans in the loop. Someone still has to decide what should be built, what constraints matter, what risks are acceptable, and whether the result actually solves the right problem. That work can’t be automated away, because it’s grounded in judgment, context, and accountability.

So yes, developers, as we once knew them, are dying out.

But long live developers. 👑

Interested in learning more about how we help devs in this new era? Try CodeRabbit reviews and Issue Planner today!